Using Chinese Romanization Systems to Determine Jurisdiction

Translations of Chinese into English use one of several standard romanization systems. The same term in Mandarin could look different when written in Latin script depending on the system used. Different jurisdictions endorse different official standard romanization systems.

The two most common systems for writing Mandarin Chinese in Latin script are Pinyin and Wade-Giles. Pinyin was developed and is used by the People’s Republic of China, whereas Taiwan (Republic of China) historically has used Wade-Giles.

By identifying the romanization system used, it is possible for researchers to determine the jurisdiction an individual or company name is most likely affiliated with.

This article provides researchers with:

- Context on Pinyin (associated with People’s Republic of China)

- Context on Wade-Giles (associated with Taiwan, Republic of China)

- Advice on how to quickly differentiate between the two

- Examples of names written in both systems

Where Pinyin is used

Pinyin was created and implemented in the mid-20th century by the government of the People’s Republic of China to facilitate literacy among China’s population, and gained widespread use from the 1950’s onward.

The Republic of China, also known as Taiwan, made Pinyin the official government standard romanization system in 2009, though individual citizens are allowed to choose to have their names officially transliterated using alternative systems.

If an individual or company’s name is romanized using Pinyin, they were most likely either born or created in mainland China after 1950, or in Taiwan after 2009.

Where Wade-Giles is used

Wade-Giles was developed in the 19th century by two British translators of Mandarine Chinese, Thomas Francis Wade and Herbert Giles.

Wade-Giles was used to romanize terms in mainland China prior to the 1950s, and was the official romanization system used in Taiwan (Republic of China) until 2009. Many companies and individuals in Taiwan continue to use Wade-Giles when romanizing their names.

If an individual or company’s name is romanized using Wade-Giles, they were most likely either born or created in mainland China prior to 1950, or in Taiwan before 2009. Most exceptions to this rule are Taiwanese individuals or companies that continue to use Wade-Giles after 2009.

Differentiating between Romanization systems

When looking at names of individuals, the fastest way to determine which romanization system is being used is to look for hyphens.

Wade-Giles uses hyphens to separate syllables within the same term or given name. Pinyin does not use hyphens.

Since most given names in Mandarin Chinese are two syllables long, they will be separated by a hyphen when using Wade-Giles, but not when using Pinyin.

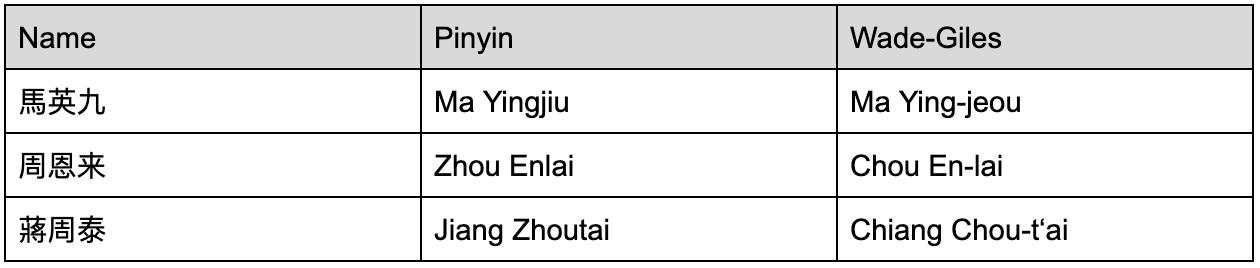

Examples of name variation based on romanization system:

In occasions when names are single syllables long, or hyphens would otherwise not be used, it is still possible to differentiate romanization systems based on the letters used.

There are a number of online resources to assist with both Pinyin and Wade-Giles romanization. These resources can be used to find an exact match of all terms romanized using either of these systems.

For faster identification, both systems contain some unique letter combinations that do not appear in the other. Spotting these differences can allow researchers to quickly identify the system the term belongs to – and by extension the jurisdiction or time period most associated with them.

Unique to Pinyin:

- zh (sounds like “j” in “John”)

Example: Zhang Ziyi

- q (sounds like “ch” in “cheese”)

Example: Li Keqiang

- r (sounds like “r” in “run”)

Example: Renminbi (RMB)

- x (sounds like “sh” in “should”)

Example: Xi Jinping

Unique to Wade-Giles:

- hs (sounds like “sh” in “should”)

Example: Hsiao Ching-t’êng

- sz (sounds like “s” in “Sid”)

Example: Szechuan

- ts (sounds like “s” in “kids”)

Example: Tsai Ing-wen

- ê (sounds like “e” in “end”)

Example: Chêng Hsiao-liu

- ’ (apostrophe appearing mid syllable)

Example: Ch’eng Mao-yün